Fyre Festival, the now-infamous failed music festival from the spring of 2017, has gained attention recently due to two documentaries released in January of this year. These documentaries shed light on the fraudulent behavior of Billy McFarland, the founder of Fyre Media Inc. and Fyre Festival LLC. While outright-falsified information may not have been able to be debunked, could any investors have foreseen what would happen?

The Prescient Operations team decided to find out.

The Task: In one hour, using only the Fyre Festival investor pitch deck and information available prior to when the festival occurred, members of our Operations team conducted due diligence research on behalf of a hypothetical, potential investor.

The Input: We asked experts from our Due Diligence Practice to weigh in on our findings, based on their industry experience. While we are quite strict about providing our due diligence clients with facts and analysis, rather than opinions or recommendations, we made an exception for this hypothetical case.

The Outcome: After analyzing investor materials, social media posts, and other open source resources, one thing is clear: had investors conducted their own due diligence, it’s likely they would have seen the writing on the wall.

Too Good to Be True?

Source: Scribd

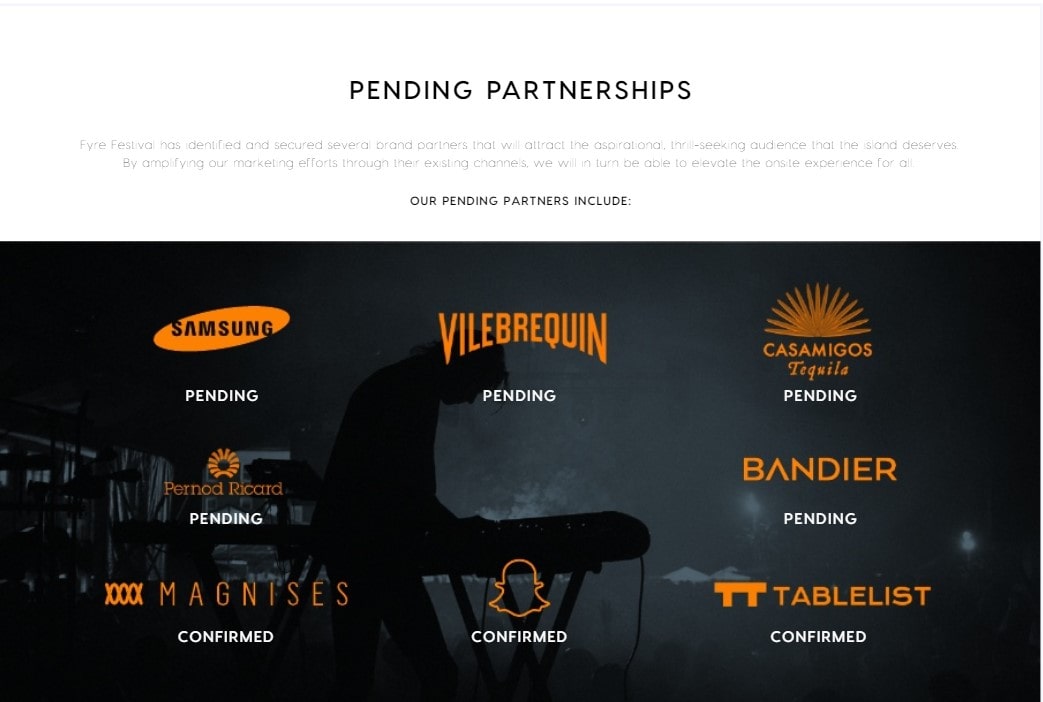

In January 2017, less than four months before the festival was set to begin, McFarland created a Private Placement Memorandum (PPM) to distribute to prospective investors of Fyre Media and Fyre Festival. This deck contains an interesting combination of true, false, and exaggerated information.

The PPM stated that since 2016, “thousands of offers representing tens of millions of dollars of performance and appearances have been made and accepted with Fyre.” (After the festival, it became clear that only 60 bookings totaling $57,443 were confirmed and paid.) The PPM also claimed that Fyre Media had “been given $8.4mm of market value land on Black Point, Exuma”—another fact that turned out to be untrue. The actual location—discoverable prior to the event—turned out to be a plot of land on Grand Exuma, the largest of the Exuma islands. Numerous slides regarding promotion of the festival list the alleged involvement of social media influencers and celebrities, who did, in fact, do so through Instagram posts and videos.

The deck as a whole relies heavily on flashy imagery, misfocused emphasis, and overhyped achievements. Information about the actual execution of the event is vague or glossed over. When it comes to making investments, entrepreneurs will always try to upsell their value. Questioning McFarland early on about the specific details surrounding the execution of the festival (e.g., supply chains, licensing, logistics) might have revealed that he was in above his head.

A Cascade of Red Flags

Source: Scribd

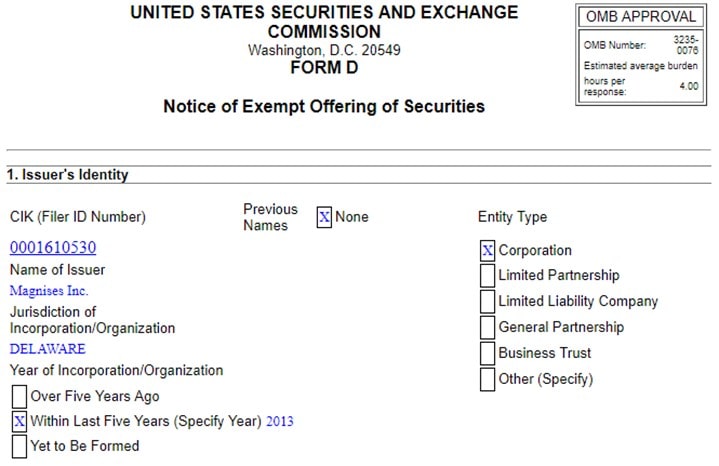

Magnises was, in fact, another business run by Billy McFarland. U.S. Securities and Exchange records from 2014 list him as the company’s Executive Officer and Director, and the company itself was founded in 2013. Despite (or perhaps because of) its recent founding, the company quickly found itself the subject of legal action and media scrutiny. In June 2015, McFarland was sued by the owner of the townhouse he rented and used to host Magnises events. The landlord sued for $100,000 in damages for three months of repair work. Additionally, in January 2017, the same month the PPM was distributed, a Business Insider article was published that discussed several complaints from members of Magnises, including failure to fulfill ticket requests, cancelled trips, and early charging of renewal fees.

Magnises is one of only two companies the deck mentions under McFarland’s corporate experience. The other company, Spling, also provides a significant source of information. Research into Spling yields a 2012 interview with McFarland that states he began working on the company in 2011 “during his freshman year at Bucknell.” He dropped out that same year to work at Spling full-time. When asked about his decision, McFarland said, “it was pretty unrealistic to leave school one day and expect…to succeed in a city like New York the next.”

From these findings, a picture of McFarland begins to emerge: he was an unseasoned entrepreneur, prone to impulsive decisions and unrealistic expectations. While some investors may have been dissuaded by this information, taking risks is part of the process—it’s likely some investors would have continued to participate at this point. But by the end of March 2017, the warning signs should have been too big to ignore.

Social Media Due Diligence: Diamonds in the Rough

According to documents from the SEC, McFarland was still seeking investors as late as April 2017, the same month the festival was scheduled to take place. Though social media buzz around the event remained mostly positive, cracks in the façade were becoming apparent.

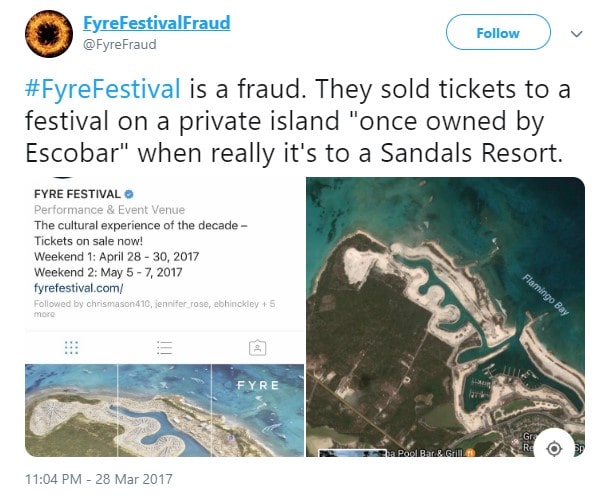

On March 28, 2017, a Twitter account was created with the handle @FyreFraud. The account tweeted worrisome information regarding Fyre Festival, such as discrepancies as to its actual location. Though marketing boasted the event would take place on a private island once owned by Pablo Escobar, posts by @FyreFraud revealed a different story. The festival would actually take place on a piece of land north of a Sandals Resort on Great Exuma, a frequent tourist destination.

Source: Twitter

The account also retweeted articles by the Wall Street Journal and New York Post that reported on the possible financial troubles of Fyre Festival. In addition to questions on Twitter and Instagram, other individuals on TripAdvisor raised questions about the event’s legitimacy as early as April 6, 2017.

Social media is an underutilized tool in the due diligence process, in part due to the sheer volume of information available. Knowing how to filter and comb through vast amounts of data could have saved last-minute investors from their involvement in the doomed venture

Hindsight is 20/20

Especially frustrating is the fact that some investors believed due diligence had been conducted. According to SEC documents, McFarland claimed that a venture capital firm had “completed its due diligence process and decided to invest more than $10 million in Fyre Media.”He was blatantly lying: after he failed to provide the firm with certain documents, the firm refused to invest. However, this claim likely swayed several investors who took McFarland at face value.

When it comes to investing money, it’s risky to rely on someone else’s word. Knowing where and what to look for during due diligence can make a difference between falling for a scam and sniffing out the fraud. Conducting your own due diligence, or hiring an expert to do so, is an investment of its own—one with much better odds.

Matt Kiernan is an Associate in Prescient’s Due Diligence Practice. He has a background in Finance from the University of Notre Dame.