Conducting due diligence on a Chinese subject for regulatory compliance purposes is no easy task, one that can frustrate even the most seasoned analysts. So why does China-focused due diligence prove so difficult, and how can firms better prepare for mitigating risks in this region?

It’s a crucial question given China’s increasing prominence in the global economy and its concurrent status as having a relatively corrupt business environment. In its 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index, Transparency International ranked China as 77th out of 180 countries in terms of corruption, giving it an index score of 41/100. Additionally, China leads the world in the number of Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) enforcement actions levied against companies operating there.

With China’s economy growing rapidly and many American companies looking to do business with potential partners, it’s critical for firms to conduct due diligence on these individuals or companies using native language sources. And yet, given the nuances and intricacies of Mandarin Chinese, this is easier said than done. So what, exactly, makes conducting Chinese-language due diligence so strenuous and how can firms better prepare for the challenges they’ll face in the region?

The Chinese Language is Inherently Difficult to Learn

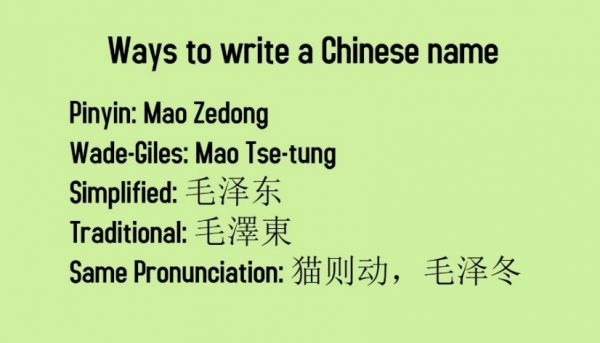

Figure 1—As demonstrated above, given differences across Chinese character and Romanization systems, there are multiple ways to search the name “Mao Zedong” when conducting due diligence.

The Foreign Service Institute (FSI) has ranked languages by how difficult they would be for a native English speaker to learn. Chinese is ranked among a few other languages in the most difficult category, which the FSI indicates would take 88 weeks (2200 hours) to learn.

Part of the reason for this is that, unlike English, Chinese is a character-based language. In order to simply read a Chinese newspaper, a reader needs to have memorized between 2,000-3,000 different characters. What is more, the educated Chinese reader knows around 8,000 characters, each with a separate pronunciation and meaning. The characters themselves give very few clues to their pronunciation and must be learned through pure memorization. Given that online Chinese resources rarely, if ever, provide an English translation, comprehensive due diligence on a Chinese company or individual must necessarily be conducted with the proper Chinese-language training.

Variations Across Character and Romanization Systems Complicate Online Research

Chinese is a language with many homophones, differentiable by the unique characters that are used to represent syllables sounding the same, but have different meanings. With that said, distinctive regions in the Chinese-speaking world write these characters differently. While mainland China has adopted a “Simplified” written Chinese character system, Hong Kong and Taiwan still maintain a “Traditional” character system that a Mainlander would find difficult to read and understand. With regard to conducting China due diligence, this means that an analyst would need to be at least somewhat familiar with both systems to conduct truly comprehensive research.

These different written systems do not stop at the Chinese characters themselves, however. There are also at least two main systems for Romanizing Chinese characters: “Pinyin” and “Wade-Giles.” Similar to above, Mainland China will typically use the Pinyin system for transliterating Chinese characters, while Hong Kong and Taiwan utilize Wade-Giles. Again, a China due diligence researcher will need to be familiar with both in order to fully vet a Chinese company or individual.

In terms of the implications for the due diligence process, what these multiple systems mean is that researchers must consider all of the different ways an individual or company’s name can be written in order to be as comprehensive as possible. As Figure 1 illustrates, in the case of China’s former leader, Mao Zedong, there are at least four different ways this name can be written across Greater Chinese regions and cultures. When crafting search strings, analysts must therefore search all of these names (in addition to any English language aliases) to make sure no critical information is missed.

Access to Information is Purposefully Opaque in Mainland China

It is evident that in order to conduct due diligence on Chinese individuals and businesses, a researcher must conduct searches in the Chinese language. Because many documents, especially from the Chinese government, are simply not available in English, a deep knowledge of the Chinese language is necessary to uncover basic biographical or business registration information. As Figure 2 demonstrates, even national-level business registration databases in the mainland are only searchable using Simplified Chinese characters. The Chinese central government purposefully makes such resources difficult to search for non-Chinese speakers. There is no centralized public records office, and thus legal or licensure information often needs to be conducted at the provincial level, across many multiple, fragmented databases.